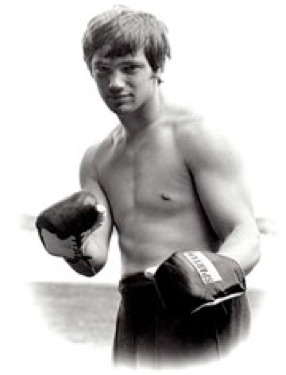

He was considered the complete package, a matinee idol who could box, punch and move on his feet as if the ring were a dance floor, and the world wasn't going to let him walk away from any of it, not this rare combination of grace, finesse and pure savagery.

He was a natural, with the God-given ability to jab, hook and punch while gliding on air, in and out of an opponent's range, strafing him with hooks and uppercuts _ sledge hammers to the body and head _ and then retreating as effortlessly as he had arrived.

Want a donnybrook? He could punch and take a punch. And opponents often found that even toe-to-toe he could be as elusive and difficult to hit as bees in the air.

"If I could have taken a punch like he could and punched like he could,'' I would have been a world champion,'' Del Flanagan was quoted as saying. Flanagan knew whereof he spoke, having fought and defeated a number of former world champions, even reigning champs in nontitle bouts during his illustrious career.

The subject of this attention, of course, is Pat O'Connor of Rochester, Minnesota, a Golden Boy before Oscar De La Hoya was even born.

"He was good enough to have been a world champion,'' said fellow boxer Gary Holmgren, who sparred with O'Connor on occasion.

A world championship was expected of O'Connor, by anyone who saw his amazing skills.

Precocious, a child prodigy, O'Connor won a national Golden Gloves title as a baby-faced 16-year-old and immediately became an irresistible target for the sycophants and denizens of the sport. He was an advertiser's dream with ticket sales a natural part of his very constitution, and everybody from the bottom on up wanted a piece of this hot commodity.

Pat O'Connor's future was mapped out for him when he was a teenager, prearranged like marriages in other cultures, dictated by the desires and wishes of people in his life, everyone who wanted a ride on the promise wagon. "I was raised to be a world champion,'' O'Connor recalled.

Nobody with that much natural talent and charisma could be ignored, and the many forces in the brutal and avaricious occupation of boxing were often too big and impossible to withstand.

It all began for him at age six or seven on the floor at home. "My dad started us out,'' O'Connor recalled. "He'd get on his knees, with a couple of pillows and tiny boxing gloves and got us going.''

It was simple matter from there to the Silver Lake fire station in town and then the Rochester Golden Gloves program, the doorway to the big stage at the time, the Minneapolis Auditorium where the champions of the Upper Midwest Golden Gloves tournament would advance to the national tournament. Under the glare of that spotlight O'Connor's remarkable abilities were introduced to a wider boxing audience, and the scrum to claim a piece of his flesh began.

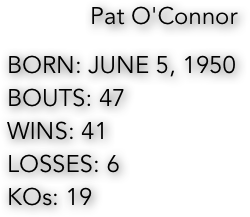

He was one day past his 18th birthday when he fought his first professional fight in Mayo Civic Auditorium, quickly dispatching Muhammad Smith. He was 28 when he fought for the final time, ending a streak of three consecutive losses, and he completed his career with a 41-6 record that included 19 knockouts.

Most boxing experts thought that O'Connor was a natural middleweight, although he frequently fought as a light heavyweight and took on bigger opponents.

He was undefeated at 31-0 when he met Andy Kendall, a top-ranked light heavyweight, in September of 1972 at Metropolitan Sports Center in a bout most observers fully expected him to win. In their minds, O'Connor at his best was simply too quick, too mobile for the flat-footed and plodding but rugged Kendall. They did not see him at his best that night, however. It was O'Connor who was flat-footed, dead on his feet and an inviting target for Kendall's cement hands. O'Connor was stopped in seven rounds.

Later, he lost twice by decision to Denny Moyer, one of the best middleweights of his time. "I thought I beat him one of those two,'' O'Connor recalled. "I guess it was a matter of opinion. But he was the best I ever fought.''

Truth be told, O'Connor had never wanted what the world wanted for him and had survived a decade or more on his enormous talent alone, without none of the passion necessary for something as brutal and unforgiving as the boxing ring.

"I was sick of it at a young age,'' O'Connor revealed. "After I won the National Golden Gloves I was already tired of it, and I wanted out.''

The money, glamour and people around him kept the fantasy going even though it had never been his dream. "The business pressures and the money involved, that's what kept me going,'' he said. "I actually tried to quit. I probably had one or two pro fights and decided that I wanted out...but.''

So, there it is, after these many years, the truth about Minnesota's 'reluctant' champion, from the champ himself, a story not unlike so many others in so many other professions. The world sometimes chooses a person's path when it is not the road he himself wants to travel. The scenery along the way holds him to that path and it is often too late to return and take another.

Pat O'Connor took that road because he heard the siren call of those around him, all of us who demanded that he display those awesome physical gifts no matter what the cost to his spirit and his psyche. The show must go on because the public demands it.

His remarkable talent and physical gifts were joys to behold for anyone who appreciates the beauty and poetry of a sport absolutely violent and unforgiving at the same time. They were intoxicating gifts to behold along with the man who possessed them; a man astonishingly nimble, quick and graceful on boxing's dance floor, and a cherished member now of Minnesota's Boxing Hall of Fame.