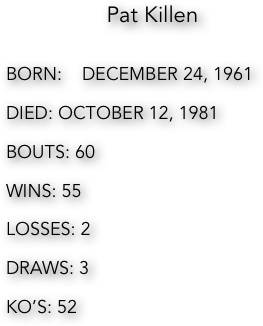

Most historians of the sport cite 1859, the year after

Minnesota became a state, as the beginning of boxing

here, with most of its participants coming from

elsewhere in the nation. Among those pioneer fighters

was heavyweight Pat Killen, a product of suburban

Philadelphia, who relocated in St. Paul sometime

after turning professional.

Killen was raised in Hadington, Pa., and was known

for a knockout punch after becoming a veteran of

street fights in the city. The record books indicate that

he turned to professional fighting in 1883 at the age

of 22 although he most likely started even younger.

Known as the Cyclone of the Northwest, Killen scored

knockouts in 52 of his 55 victories.

Killen became a friend and student of boxer Jack Burke,

from whom he learned the art of counter punching,

a technique he mastered, and in 1883 signed with

manager Parson Davies, relocating in Chicago to work

under Tom Chandler, one of the leading trainers of his

time. Davis had recently split with Patsy Cardiff, a top

heavyweight contender, and found a new headliner

in Killen.

Killen fought for the first time on July 6, 1883,

knocking out John Howard who was also making his

professional debut. He quickly became identified by

boxing writers who saw him as the fastest heavyweight

in the ranks and over the next two years scored

eight additional knockouts, mostly over inexperienced

fighters from the friendly confines of Philadelphia

where he was raised.

Davies, who was friendly with Twin Cities promoters

John Barnes and Pat Conley, displayed his managerial

skills by guessing that Kellen would be a popular

fighter in St. Paul because of its large Irish population.

A match was made against unbeaten Joe Lannon of

Boston and the date settled upon was November 8,

1885. It was to be held outside at a large, fairly flat

piece of land known as Silk’s Grove on the shore of the

Mississippi River and named for owner John Silk. The

location was beyond the jurisdiction of the St. Paul

police and the Ramsey County sheriff. Nonetheless,

the promoters were taking a chance with Mother

Nature. Early November could bring cold, wind and

rain, even snow.

Four days before the fight, Killen arrived in St. Paul by

train and was greeted by a large crowd at the depot

eager to see the knockout artist. Patsy Cardiff, who

held the Northwest heavyweight title at the time,

was living in Minneapolis and stated that he wanted

to meet the winner of the fight.

A paddleboat left the Chestnut Street wharf in St. Paul

filled with patrons along with the boxers and their

camps and sailed south to Silk’s Grove. A ring was set

up upon their arrival and a referee appointed heavyweight

boxer Bill Wilson, who would become the first

African American to officiate a fight in Minnesota.

Killen was attired in pink tights and Lannon in brilliant

blue tights when they toed the line at 4:01 p.m.

Lannon commanded the first three rounds before

Killen took over, wearing down his opponent steadily

before flooring him in the ninth round. Lannon was

knocked down a total of six times when Wilson

declared Killen the knockout winner.

In a scenario that Don King would have loved, the

local promoters claimed that the crowd for the fight

was comprised largely of gate-crashers so there

wasn’t much in the way of ticket sales. Killen received

a paltry $34.50 of the $300 he had been promised.

Lannon was paid even less, $25. Killen, Davies and

Chandler promptly climbed aboard the 8:40 p.m.

train for Chicago.

Killen fought six rounds on March 6, 1886 against

Pat McHugh in a bout ruled no contest due to

McHugh’s unwillingness to engage actively in

the fight. Killen had left Davies by this time and

moved to St. Paul where he married shortly

thereafter. From a wealthy family, Killen opened a

large saloon on West 7th Street in St. Paul and soon

thereafter became one of its best customers himself.

Twenty-four of Killen’s fights were staged in

Minnesota, most of them in Minneapolis or St. Paul,

although he fought in Duluth and Rochester as well.

As alcohol took over his life his run-ins with the law,

for assault and various other infractions, became more

numerous, and at one point he left Minnesota for

Canada with no evidence that he ever returned. In the

meantime operation of his saloon in the Seven Corners

area was taken over by relatives.

Killen’s record included only two losses, although one

of them, by disqualification to Mervine Thompson in

Cleveland, Ohio, bordered on fraud. The referee for

the fight was a relative to Thompson. Each time Killen

knocked Thompson down he was given a prolonged

count. When angry patrons stormed the ring in protest,

the referee disqualified Killen.

Six months later Killen set the record straight, knocking

out Thompson in a rematch, this one in Omaha with

not a relative in sight. He lost by seventh-round

knockout to Joe McAuliffe on September 11, 1889.

That loss was accompanied by reports that Killen was

intoxicated when he entered the ring. Following a wild

swing at his opponent he hit the mat and dislocated a

shoulder. Killen would fight only twice more, winning

by disqualification against Joe Sheehy at the Jackson

Street Rink in St. Paul in one of the fights. Killen was

winning so easily that Sheehy became enraged. He

threw Killen to the mat four times, biting him in the

chest, the leg and the stomach. Referee Dick Moore,

who disqualified Sheehy called those actions the most

outrageous he had ever seen.

Killen would fight once more, nearly eleven months

later, ending his career with a knockout over Bob

Ferguson in Richardson, Illinois.

Ten days later Killen died in Chicago from an infection.

He was twenty-nine years of age. His brother Denny

returned Pat’s body to Philadelphia for burial. Three

and one-half months later, Denny died from the

same illness that killed Pat. He was buried in the

same grave site on top of his brother.

Now, one-hundred and twenty-five years later, Pat

Killen will get a second memorial, as an inductee in

the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.