He had the lung capacity of a deep-sea diver and a jab

that flicked with the repetitive quickness of a black

mamba’s tongue, attributes that allowed him to survive

in the jungle of professional boxing without the power

possessed by many if not most of his opponents.

The jab he learned from his father. His lung capacity was

a direct product of long-distance running – marathons,

in fact – that enabled him to stay on the move and

withstand a torrid pace if necessary against many

stronger, tougher opponents.

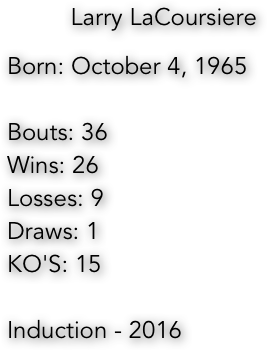

Larry LaCoursiere was known as Lightning Larry

because of his ability to stay on the move and avoid

the punishment taken by less mobile fighters.

“He was fast and he was evasive,’’ said long-time

friend Mike Evgen, who lost on points to LaCoursiere

for the Minnesota super lightweight title.

LaCoursiere disarms many people upon meeting him for

the first time because they know he was a professional

fighter who fought some of the top names in his weight

division, during a career that spanned ten and one-half

years. Yet, he is basically mild mannered and selfeffacing,

surprised at the attention he sometimes gets

from strangers, puzzled that someone remembers him

at all. He was stunned, as an example, upon learning

he was chosen for induction into the Minnesota Boxing

Hall of Fame. “I still can’t believe it,’’ he said, three

months after learning of the award.

LaCoursiere knocked out Remuse Caffee to begin his

professional career on October 24, 1990 at Roy Wilkins

Auditorium in St. Paul. He retired after being stopped

on April 22, 2001 by unbeaten WBA - NAB super

lightweight champion Hector Camacho, Jr., at

Fantasy Springs Casino in Indio, California, compiling

a 26-9-1 record that included 15 knockouts during

the decade-plus that he boxed professionally.

LaCoursiere was highly successful as an amateur

fighting for the Hastings Golden Gloves team, winning

five St. Paul titles and three Upper Midwest titles that

took him to the National Golden Gloves tournament

each time. It was during those trips, Evgen recalled, that

the two fighters cemented what has become a lasting

friendship, despite sometimes long intervals between

personal exchanges.

Evgen staged an amateur boxing show in Oakdale last

June and invited LaCoursiere to attend as one of the

newest inductees in the state’s boxing hall of fame.

“We hadn’t talked in a long time,’’ Evgen recalled, “but

that day it was if our friendship picked up just where it

left off. He’s just a super guy, a real class act.’’

Loads of respect still clearly obvious, despite that loss

to LaCoursiere in October of 1995. “I was at a bad point

in my life right then,’’ Evgen recalled, “but he was just

better than I was that night.’’

The passage of time has not dimmed Evgen’s memories

of LaCoursiere’s attributes. “He always had good movement,

good footwork, was difficult to hit.’’

The respect between the two fighters, even two

decades later, clearly has not diminished with that

passage of time. When Evgen was enshrined in the hall

of fame in 2011, LaCoursiere was in attendance. When

LaCoursiere was informed of his selection to the hall of

fame, one of the first persons he informed was Evgen.

“I am definitely coming to this one,’’ Evgen said. “I plan

to be there for his induction.’’

It has become a time of reflection for LaCoursiere, a

time for reliving old memories, including the numerous

stories associated with his introduction to boxing, as

a youngster whose family had relocated to Hastings

from Cottage Grove.

His father, Jerry, had boxed in the Marines and, for

various reasons, started coaching his sons in the sweet

science some time after the move. “One of my older

brothers had been mugged by some thugs in town,’’

as Larry recalls, “and dad became sort of a vigilante

after that.’’

The jab was one the first things Larry learned from his

father once he was old enough to join his brothers in

the gym. “I was never a power puncher, so I had to have

that jab to get by,’’ he recalled. “A quick, straight jab...

that’s what I always tried to throw. I would have been

screwed without it.’’

LaCoursiere played football but was, as he explained

it, “kicked off the team” after informing his coach he

intended to fight in a boxing tournament in Wisconsin.

He also ran on the track team, at 1,600 and 3,200 meter

distances. He progressed to marathons, including

the granddaddy of those torture tests, the Boston

Marathon, but ran his last 26-mile endurance run in

2004. Running is not part of his life any longer since

breaking an ankle in 2008. “Arthritis,’’ he explained.

LaCoursiere was stopped in three consecutive fights

before getting his career back on track in August of

1994, stopping Rick Caldwell in a bout at Mystic Lake

Casino, ironic in the sense that his hall of fame induction

is scheduled for the very same location.

He approached the fight against Evgen having

been stopped three months earlier by future world

middleweight champion Ronald Winky Wright.

Thoughts about retirement started to creep into his

mind after losing a split decision in June of 1998 to

Johar Aby Lashin for the IBC welterweight title. A year

earlier he had lost on points to Julio Cesar Chavez.

“Lashin was certainly someone I could have beaten

and would have in another time,’’ he recalled. “It was a

split decision but I got beat up. I had three or four cuts,

something I never got before. Once that happened,

I thought maybe I’m done.’’

There were still two paydays awaiting him. He stopped

winless Andre Lovett a year and one-half later, three

months before his final fight, against Camacho in the

California desert. Yet, he had already done enough to

earn a place in the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.