The stories are told repeatedly at the dinner tables and in the living rooms of the Irish, stories about their prizefighters who participate in such a dangerous and unforgiving sport yet the kindest of souls you could ever imagine outside of the ring.

It is a common enough theme to suggest there must be truth in it, some validity concerning men who will render you unconscious inside of the squared circle but give you the shirt off their backs on the city streets.

They will whip you beyond recognition and then pay the hospital bill, or in even more figurative terms they’ll take your head off and then pay for the hearse and the funeral.

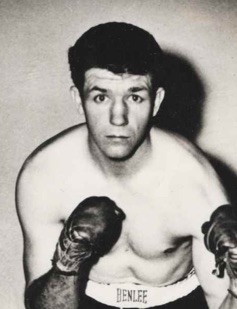

And all of that is expressed with a wink and grin in the Irish fashion. Meet Jackie Burke, a man who possessed all of those attributes and perhaps expressed best his heritage in a rather typical way:

“On St. Patrick’s Day, he wanted everyone to be Irish,’’ said his daughter, Shawna. “He was Irish through and through.’’

Public sentiment in the United States at one time held that there were only certain occupations open to Irish men: The priesthood, police work, writing or prizefighting. Jackie was both fighter and policeman and, in an unofficial fifth capacity, a man of great humor. “He loved telling jokes,’’ Shawna added.

All of that is not to suggest that he was indeed approaching sainthood. He was, in fact, married three times. Be that as it may, he made a mark on numerous youngsters who occupied the gymnasiums of which he became a part at the Altoona campus of Penn Staten University where he worked as a security officer in retirement.

“He would teach them boxing skills,’’ Shawna recalled. “He fought there once (an exhibition) trying to stir up interest in the sport.’’

Burke became part of an unusual bit of Minnesota history, fighting three fights consecutively against two brothers that involved winning the Minnesota middleweight and light heavyweight titles.

On December 4, 1947 he won a unanimous decision over Hall of Fame fighter Mel Brown for the Minnesota middleweight title. Two weeks later he kayoed Buzz Brown, Mel’s brother, to defend that title. Three weeks later he fought Mel Brown again, that time for the vacant Minnesota light heavyweight title, winning a narrow and somewhat controversial decision, by one account.

Minnesota Hall of Fame writer George Barton captured the action with the following words:

“Jackie Burke, Grand Rapids, Minn., added the light heavyweight championship of Minnesota to the middleweight title he won several weeks ago by being awarded an unpopular split decision over Mel Brown of St. Paul in a bruising 10-round fight before some 7,500 fans Thursday night at the Auditorium.

“The majority of spectators thought Brown won and booed the decision vociferously for five minutes after it was announced. This writer thought Brown won by a margin of 94 points to 90, but two of the three officials decided otherwise.

Referee John Sokol awarded the decision to Burke,94-93, Judge John De Otis voted for Burke, 94-92, while Judge Britt Gorman declared Brown the winner by a margin of 98-92.

“Brown scored the only knockdown when he dropped Burke to his haunches with a clean right hand punch to the chin early in the first round.”

The terrible scourge of his chosen sport took over in his Burke’s later years, dementia, Shawna recalled, and he became a different man in the making of a story told over and over again in today’s sports world. Yet, he had long since established himself as a fighter of immense skill and determination with a willingness to fight in the other guy’s backyard where it often required a knockout or a one-sided whipping to sway the hometown judges. At the very least, a visiting fighter could leave little room for doubt if he hoped to emerge a winner.

In another unusual twist to his career, Burke lost in his professional debut, a bout typically carefully arranged to insure that fighter begins on a positive note. He lost that bout on points to one Russell Baxter in Duquesne Gardens, Pa.

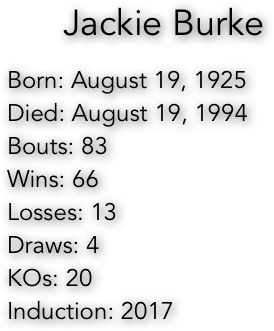

Nonetheless, Burke went on to a solid career, fighting across the country while compiling a 66-13-4 record that included 20 knockouts. He lost in his debut and then fought his next 19 bouts in various California cities before relocating in Minnesota to re-establish his career locally.

Even then, he took fights in Chicago, St. Louis and Miami. He stayed active, taking bouts wherever he could get them. He sparred with the greats in the game, Jake LaMotta and Rocky Graziano.

“Dad always took me to boxing when I was young but I was bored by it then,’’ said Shawna. “As I got older I wished I had paid more attention.’’

Just the same, Jackie Burke did not allow this daughter to go without learning some of the finer aspects of the sport.

“I would rather have been playing with my Barbie dolls,’’ Shawna said, “but whenever he got the chance he would show me how to jab and punch and throw a left hook, then later the uppercut. Whenever he got the chance. It was constant.’’

What she remembers as well were the St. Patrick’s day celebrations. “He was proud of his heritage,’’ she said. “St. Patrick’s day was like Christmas to him. He loved to tell jokes.’’

And not just to family members or friends “He’d stop people when he was out and talk to them. He loved doing that, and people loved him. He loved telling them stories,’’ Shawna said. “He’d give a stranger on the street the shirt off his back. He always picked up hitchhikers and my mother would tell him not to do that when he had me in the car with him.’’

So, it seems, Jackie Burke passed all of the requirements for recognition as an Irish boxer and, certainly, more than needed to make him a member of the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.