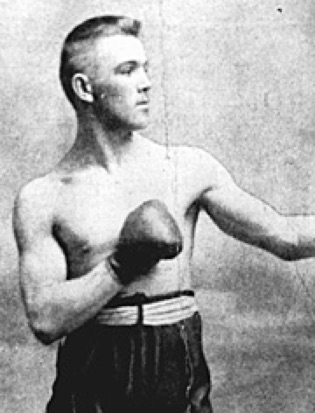

His record was the stuff of legends. A perfect unblemished record in an era of iron men who fought with 4 oz gloves, and many times went to a finish. And in a time when news traveled slowly, his gifts were so well-known that the 140 pound Lightweight/Welterweight had to fight Heavyweights just to get action, and when he blew through them in two rounds as opposed to his customary one, he took to fighting under aliases. For the man sportswriters said could beat you with his stare alone, had become a legend in his own time. St. Paul's Charley Kemmick was quite simply…perfect.

Perhaps it should have been a sign of things to come when in his first professional fight he almost killed Dick Moore, a man that would in the future be the #2 Middleweight in the world. Moore was so badly out, that he was hospitalized and hanging on the brink of life and death. Kemmick, just 16 years-old, sat scared and in awe of his own abilities in a 9'x9' jail cell in St. Paul awaiting possible murder charges. When Moore emerged from his coma, so too, did the beginning of the legend of Charley Kemmick. When he began working out at the Twin City Athletic Club with the immortal Danny Needham, the renowned Lightweight Champion of the Northwest said, "This kid is so naturally good at fighting it's frightening.”

Needham may have been prophesying that day, as after sparring with two other men and nearly killing them both just a few days apart; Needham was the only one willing to work out with him. Some said he was a loner, and though it is true that he trained primarily by himself, but it is also true that few were willing to spar with him out of fear of being killed, as the great Charley Johnson once admitted. This fact only makes historians of 19th Century boxing more in awe of Charley, as the man rarely had access to sparring partners to perfect his moves.

In just his fourth time in the ring, he knocked out two men in the same night, just 10 minutes after one another; one of them in just 48 seconds. This caused his aura to grow even more. But when he was outweighed by 27 pounds and fought Ed Mohler a few months later, knocking him cold in 20 seconds flat with the first punch he threw, Kemmick's name was on fire and had to leave the state to find fights; and for the first time, had to begin denying his identity and taking on false names to stay busy. While in Wisconsin, he fought Heavyweights Frank Kellar and John W.Curtis. In meeting Kellar, he knocked him out 3 different times in the 4th round alone, yet the referee refused to allow a knockout out of fear of being arrested given the politics of the time, and allowed Kellar to be revived each time, thus resulting in the fight being ruled a Draw after 10 rounds. After the fight, Kellar collapsed and was hospitalized for head trauma and was close to death for two weeks. Curtis too, was knocked out, but in just two rounds. Unable to secure fights, he joined forces with the legendary boxing manager and promoter, Parson Davies, for a tour out west. While in Denver, Davies tried to get World Lightweight Champion, Jack McAuliffe, to put up his world title and a side-bet of $20,000 (almost $500,000 today) and Davies swore that McAuliffe was interested until he found out Kemmick was the opponent, and then refused to sign for the fight. Davies simply could not get him action, as he was too well-known, so they began fighting in Texas under the name of Charles Hearld, and Davies and Kemmick traveled from town to town offering $500 to any man that could stand before Kemmick for more than four rounds. They never had to pay out. Kemmick went a perfect 11-0, winning all by knockouts, including almost killing yet another fighter. This time it was Tom Standard, a Heavyweight whom Kemmick put in a hospital for weeks with a coma and a fractured skull. Standard barely survived, and yet he would not be the only one almost killed by Charley on this tour. While fighting Jimmy Foster in San Antonio, he knocked Foster unconscious and put him in a coma for two days, almost taking his life. While on this tour in 1890, Kemmick contracted a severe chest cold, but rather than resting, he continued on, training in dusty gymnasiums and training while weakened. He got sicker and sicker, until finally they had to return to Minnesota to allow Charley to get better. He didn't know it then, but he had contracted Tuberculosis, and it slowly began to consume him.

He later returned to Minnesota, where his management twice tried to get the recognized Welterweight Champion of the World, Tommy Ryan and his manager Lou Houseman to agree to fight for Ryan's title. Both times, they adamantly turned the offers down. Kemmick immediately signed to face the highly regarded Jimmy Scully for the Welterweight Championship of America, the next best title to being the World's Champion. Scully was a very good boxer from the East; so much so, that betters from Boston wired $3,000 to St. Paul on Scully winning by kayo-quite a sum, as adjusted for inflation today, that is more than $70,000. The fight wasn't even close, as Kemmick had been waiting for this opportunity and seized it, knocking Scully out in the 2nd round, with a single right cross to the chin, and winning the Championship of America and a purse of $1,000. Ryan and Houseman were there ringside, and Twin City Athletic Club matchmaker, Horace Libby, immediately approached Houseman with a contract. Houseman reportedly told Libby, "I wouldn't let my fighter in the ring with him for a million dollars".

A few weeks after the Scully title fight, Kemmick KO'd Joe McManus in four rounds in St. Paul, before fighting Jimmy Murphy in a 12 rounder. Murphy was reported to have run the entire night, and despite Kemmick giving him a thorough trimming and knocking him down, referee Andy Bowen, refused to issue a winner or loser, and instead called the match a Draw, which met with catcalls and boos. Shortly after this, Kemmick went on tour out west with Parson Davies and champion, Bob Fitzsimmons. While there, he began to feel sick again and had troubles breathing, yet continued on his tour. In San Francisco, he faced the highly-regarded Hite Peckham, and whipped him so easily, that no one could believe that the fight wasn't faked, as this was the same Peckham that had barely lost to the infamous Peter Maher, yet Kemmick dumped him cold in the 3rd round. The referee could not believe it, and called the fight a No-Contest, robbing Kemmick of his KO victory and his purse.

After he returned home, his condition worsened. His doctors told him the news of his disease and he spent his savings on every treatment to find a cure. He fought one last time in 1892 to Jack Wilkes, but was not himself and the papers reported on how he could barely breathe after just two rounds. Still, he pulled out a Draw and retired. He fled to Denver at the advice of his doctors to seek drier air, but died less than a week after arriving. He would never get his chance at a world title. Just when his star was shining its brightest at the prime age of 23, Charley Kemmick was dead. He always maintained that he was a perfect 33-0, and though those 5 missing fights have not been found as of his induction this year, there's no reason to doubt the claim. Worthy of mentioning, is the fact that years later in 1914, while writing for the Minneapolis Tribune, former matchmaker, Horace Libby wrote an article on Charley. In it, he states that he is often asked to compare Kemmick with the current fighters of the day. In 1914, Mike Gibbons was generally regarded at that time as the best pound-for-pound fighter in the world. Libby, a man who had seen both men fight in-person said this, "Of all the present day boxers, Mike Gibbons, in my opinion, is the nearest approach to Kemmick, particularly in ring action and manners. Yet, I think, and I am not alone in my opinion by any means, that the equal of Charley Kemmick in natural fighting ability was never born." Similarly, in a 1928 article written by George Barton, George states that he has been told by those who saw Kemmick fight, that he was the greatest pugilist ever developed in the Twin Cities. He went on to say that, "Kemmick, so my informants tell me, was to the Lightweight division what Bob Fitzsimmons and Stanley Ketchel were to the Heavyweight and Middleweight divisions." Powerful endorsements indeed.