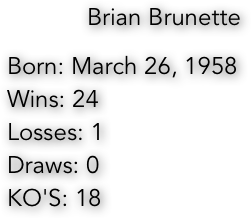

Brian Brunette was expecting a phone call, just not the one that was forthcoming. It took a few moments to set in after he hung up, and, even then, the next day he was still pinching himself, in the proverbial manner used to determine one is not dreaming.

The news was a bit overwhelming at rst. He had been elected to the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame. Slowly, reality set in. Then, he was simply on cloud nine, ying high, an altered state with which he is not unfamiliar.

After all, Brunette is a certified fight instructor and at one time, several years ago, ew a Learjet daily for a local company, delivering canceled checks for local banks, two or three times a night, from the Twin Cities to Chicago and Cincinnati.

“I’d leave St. Paul for Chicago with a load, pick one up and bring it back to St. Paul, then load up and head to Cincinnati,’’he said.“I did it all night, making ve or six stops.’’

At breakneck speed.

“Flying a Learjet is quite an experience,’’he said. “They are much faster than most planes, three to four hundred miles an hour.’’ Or faster.

His full time job these days seems a bit more aligned with the profession of boxing. Remember the Cinderella Man, James J.

Braddock? Brunette can easily identify with him, dock worker that he was. Brunette is a union marketing representative for the Minne- sota Laborers Union, a position he has held the past thirteen of the twenty- ve years he has been with that organization. So, these days he ghts on behalf of laborers, for their health care and pensions and their many other rights.

People he encounters these days often tell him that he doesn’t look like a ghter. “I tell them that I consider that a compliment,’’ he said.

Boxing, as it turned out, was not even a sport he considered while a youngster, not even in high school.

There were sports he loved more, baseball and hockey. Of those, he had a favorite, too. “I was actually a pretty good hockey player in high school, but I loved baseball more,’’ he said.

Clearly.

He wound up playing at the University of Minnesota, after starting out at Iowa Western Community College and playing in the 1977 Junior College World Series in Grand Junction, Colorado.

Primarily an in elder, Brunette began boxing as a way to stay in shape for baseball. His father had been an amateur boxer and fought in the Upper Midwest Golden Gloves tournament.

Brunette said he was originally contacted by the grandfather of baseball at the University, Dick Siebert, and then played under him and George Thomas.

Boxing entered his life almost by happenstance. He would show up frequently at the Rice Street Gym to watch his brother Al train. He was around the sport on a frequent basis yet too involved with his own athletic endeavors to imagine getting involved himself. Until, that is, Siebert issued an autumn edict to his players.

“After fall ball at the university, Siebert told

us to come back in condition for spring ball,’’ Brunette recalled. “I started training at the Rice Street Gym. My brother Al was training there.’’

His boxing debut was almost immediate. Twenty-four hours after deciding to take gym training into his life, he climbed through the ropes at Stem Hall, lling the need for someone in his weight class to fight on a card that evening.

Stem Hall was packed. “Everybody from our neighborhood was there,’’Brunette recalled. “They all knew that we had a boxing family.’’ It had started with his father, who had boxed as a young man. Upon winning an Upper Midwest Golden Gloves title, Brunette presented a gift to his father, the Golden Glove with the little diamond inset that had eluded him thirty years earlier.

So, he was able to ll in a missing piece for his dad, although it is guesswork on his part trying to determine why his dad went by the name “Tommy” instead of his given name, “Bernard.’’

“I guess he didn’t care for the name Bernie,’’ he said. Whatever the case, Brunette had discovered boxing by that point, and fought the nest ght of his amateur career in the National Golden Gloves tournament, losing a close decision to James Shuler, who later retired with a professional record of 22-1.

“He did everything just right against Shuler,’’ said his corner man for the bout,’’ Del Bravo.

“He boxed him perfectly.’’Although Shuler was awarded the decision, Bravo said it was up in the air as they awaited the verdict. “It was really a tossup,’’ he said.

Brunette’s professional debut the next year was anything but, and took place on an even larger stage. How many fighters can say they debuted as part of a world title ght. Brunette scored

a second-round knockout over Wayne Grant, the rst of twenty-three consecutive wins, in a fight that was part of the under card of the World Boxing Council heavyweight title match between Scott LeDoux and Larry Holmes at Metropolitan Sports Center.

The one loss of Brunette’s career came in Italy, for the World Boxing Association super light- weight title and he was stopped in three rounds by Patrizio Oliva.

Yet that fight is one he considers a highlight of his career. “Fighting for a world title is every boxer’s ambition,’’ he said. “Not everyone gets the opportunity. I got that chance.’’

Another bout he counts among his career highlights is a 10-round fight at the Prom Ballroom in St. Paul against Gary Holmgren, for the Minnesota super welterweight title. Brunette won the ght, with Hall of Fame referee Denny Nelson ruling it a draw. Judges Leroy Benson and Chuck Hales gave the fight to Brunette, each by a point.

Brunette, sixty-one, has other concerns these days, a family – his wife, Kim, and daughters Briarland, fifteen, and Emersyn, twelve. Both daughters attend the Convent of the Visitation in Mendota Heights and, naturally, are involved in sports, soccer, hockey, basketball.

Now he is part of an even larger family, as a member of the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.