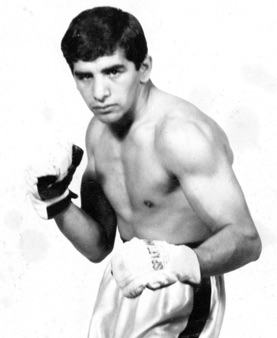

You always knew who he was, even before the ring announcer uttered a word, dancing on his toes, head bobbing up and down, gold boxing shoes and trunks underneath the serape, highlighted with a Mexican sombrero.

The wide-brimmed hat, a colorful nod to his heritage, eclipsed a handsome face beneath coal black hair and penetrating eyes that often undid opponents before a punch was delivered.

He was brash, cocky and ready to engage whoever it was in the opposite corner. This was the young, aspiring Bobby Rodriguez, third oldest in a family that produced a half dozen excellent fighters.

“I always thought he was one of the better fighters to come out of this area,’’ said long-time international referee Denny Nelson, who won a handful of Upper Midwest titles himself. “He could box. He was a good boxer.’’

Now, all these years later, Bobby Rodriguez is paying homage to the other side of his heritage, to his Indian roots, to the Aztec blood that runs in his veins.

“That’s the side he celebrates now,’’ said his wife, Sharon, an Ojibwe from the Leech Lake Reservation, where the Bobby Rodriguez branch of the family resides.

He is a man able to look back with a critical eye on what was then and how it all came to be. He made four trips to the National Golden Gloves tournament as the Upper Midwest representative during the 1960s. A fifth trip appeared in

the offing except for the presence of a rugged, little fighter from Hastings named Duane Mann. “He’s the only guy who beat me up,’’ Rodriguez now says. “Otherwise it would have been five.’’

Reminded that Mann was later killed in a freak snow storm while hunting in Alaska, Rodriguez still holds respect for that long-ago amateur opponent. “When I heard about that I bowed by head and said some prayers,’’ he responded. “I hope to see him again one day. He was a tough, good fighter.’’

Humility has a way of crowding into the makeup of former fighters with the passing of time, not as a sign of surrender but as an acceptance of a larger truth. Time often provides a wider lens on the reality of what has taken place, as it has for Rodriguez.

Much of his professional career took place on the West Coast. Many Minnesotans recall him best during his amateur days when he brought a brashness to the ring that inspired some and alienated others.

Fighting was his response to other aspects of his life and to the influence of his older brother, Kenny. “I was 10 or 11 at the time,’’ Bobby said. “Kenny came home with an Upper Midwest jacket, a trophy for best boxer and a ring with a little diamond in the center. I wanted those things, too.’’

Boxing also seemed like the answer to other problems at the time. “Bullies were also taking my money from me and beating me up,’’ he recalled. “I didn’t know how to read or write so I decided I would learn to fight, that was something I could learn to do.’’

Rodriguez was determined that the tough guys of his neighborhood would no longer take his lunch or money from him. He watched his brother, Kenny, intently. “He taught me and so did Harry Davis and Ray Wells,’’ he said.

“...a colorful nod to his heritage, eclipsed a handsome face beneath coal black hair and penetrating eyes that often undid opponents before a punch was delivered.”

His proudest moment did not come as a professional fighter but as an amateur, at age 15 when he won his first Upper Midwest title.

“I had to beat five guys and one of them was 25 years old,’’ he said. “I wasn’t old enough to go to the national tournament, but they agreed to let me because my birthday was in February and the tournament was in March.’’

Rodriguez had found a way to deal with the bullies, to keep his money and his lunch and to keep his pride, to fill in the gap for his inability to read and write. “I don’t know why I couldn’t do those things,’’ he said. “I still can’t.’’

It didn’t matter. People began patting him on the back, telling him they saw him fight and liked his style, liked his colorful attire, the way he fought. “They had me on their shoulders,’’ he recalled. “I was just a little guy and they thought I was good.’’

And he was, pumping a jab as if it were a piston powering a machine that also delivered hooks, uppercuts and body shots.’’

Minnesotans saw Rodriguez only at the beginning of

his professional career and at the tail end, when he was fighting merely for the money. The bulk of his career, during which he was the 10th ranked featherweight for a period of time, took place in Los Angeles _ in the Olympic Auditori- um. He won 20 consecutive bouts before losing for the first time, on a sixth-round TKO to Pete Gonzalez.

“That was my toughest pro fight,’’ Rodriguez recalled. “He counter-punched me..boom, boom, boom. Every punch he was faster, quicker, and the next thing I knew I was telling myself I couldn’t beat this guy. When you think that way, you fall apart and that’s what happened to me.’’

Rodriguez fell out of the rankings and returned home to Minneapolis. “I came home penniless. I couldn’t do anything any more,’’ he recalled. “I didn’t care anymore and didn’t

do what I was supposed to do. I was fighting just for the money.’’

His ten year career ended in 1977, after losing four of his last five bouts by kayo or TKO, including losses to fellow Minnesotan Rick Folstad in the last two fights.

Nonetheless, he left an impression on the sport, amateur and professional, and has found a permanent home this time in the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.