Bobby Daniels met the challenges of life with whatever was necessary at a given time, be it self resolve, resignation, grudging acceptance or simply a survivor’s understanding of his limitations in a specific instance. He could take the challenge to an adversary when need be as well.

Those abilities were allies in the prize ring, where he weathered assaults from various opponents, but outside the boundaries imposed by the Marquis of Queensberry Rules , too, where as a younger man he was sometimes constrained by his racist surroundings.

Daniels was respected as an all-around athlete in high school, and expanded that respect to the boxing ring in later years, becoming at the same time a well-known and respected citizen of Duluth, despite what had transpired earlier in his life, including a childhood in which he was shuttled from one foster home to the next.

As a high school football player in Duluth Daniels couldn’t join his teammates in the hotel on road trips, so he slept in the bus. He couldn’t eat with them in diners, so he ate on the bus. He sidestepped the insults to his humanity with as much dignity as possible, as if they were simply punches that he avoided with the mobility he displayed inside the ring.

There weren’t a handful of black citizens living in Duluth at the time, and Daniels would eventually become the most visible among African Americans in the city, a consequence of his exceptional abilities in a boxing ring where he retired as Minnesota’s light heavyweight champion after fighting for the last time against Bobo Olson on a January day in 1961.

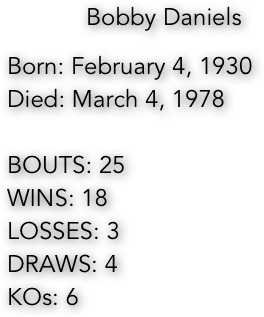

Arno Goethel wrote for the Duluth News Tribune when Daniels was a high school athlete at Duluth Denfeld and then at the University of Minnesota Duluth. Goethel was sports editor of the St. Paul Pioneer Press/Dispatch when Daniels was killed in a car accident on March 4, 1978 at the age of 48.

Goethel helped sort out some confusion following a fight between Daniels and Hall of Fame colleague Jim Hegerle for the Minnesota light heavyweight title. A mistake in addition had sent both fighters to their dressing room after the bout believing their fight had ended in a draw. That’s where Goethel joins the story, as he explained in a Pioneer Press column in the days following Daniels mysterious death.

Hegerle had won the title by stopping Joe Schmolze on March 17 1959 at the St. Paul Auditorium. Schmolze had claimed the title in a split decision over Hegerle the previous year in Roseville.

As Goethel described the fight shortly after Daniels’ death:

I was the guy who escorted Daniels to the throne. One judge scored the 10-rounder in favor of Daniels. The other judge voted for Hegerle. Jim Perrault, the referee, had it dead even in points. So it was announced as a draw and Hegerle was still champion.

However in my normal duties of covering the fight for the Duluth newspapers, I scanned the three cards.

Lo and behond, Perrault had made an error in addition, short-changing Daniels by one point in his total. I checked with Perrault. Yes, he admitted, he had made an error.

The correction was made and despite the protests of the Hegerle camp, Daniels was awarded the title.

Daniels made his professional debut on July 7, 1950, scoring a knockout over Don Cain in the Duluth Municipal Center. He ended his career on January 19, 1961, losing a unanimous decision to the well regarded Olson,who fought a wide variety of boxing’s top middleweight and light heavweight contenders during his career. Although it was the final fight in the career of Hall of Fame inductee Al Andrews, Daniels knocked him out before a home-town crowd as well.

Mark Daniels was too young to appreciate his father’s athletic prowess during his active career, but began hearing stories from friends and acquaintances in later life.

“I began hearing stories from friends of his and when I’d run into someone who had seen him fight, about how good he was,’’ Mark said.

“He really was a big deal around here and in the Twin Cities. I found that out later in life.’’

Daniels had seven children with his wife, Joyce, and, although he was subjected to racial prejudice in several instances as a high school athlete, his daughter Deb insists that her father paved the way for them to have a better life, free from the abuses he suffered.

“He really did make life easier for us. I believe that,’’ Deb said. “I got some really good jobs in my 20s. I’d fill out an application and was hired when they found out I was Bobby Daniels’ daughter. He made our lives so much better.’’

She, took, learned the most about her talented father from the parents of friends she acquired in her adolescence and as a young adult.

“Everybody talked about him. I’d go to a friend’s house and their dad would say, ‘ oh, you should seen this fight or that one.’ I’d go to the beach and someone would bring him up there.’’

Retired from boxing, Daniels started a self-defense school in Duluth, teaching youngsters in the community how to take care of themselves. Nonetheless, he didn’t want his sons pursuing boxing careers. “He didn’t want us to get into that,’’ Mark said. “He wanted us to do other things.’’

Some of the stories the Daniels family has heard about their father will quite likely be repeated during the induction banquet for the 2017 Hall of Fame class, a ceremony that will include as one of it’s newest members, Bobby Daniels himself, a man who waged winning fights inside and outside of the boxing ring and retired as Minnesota’s reigning light heavyweight champion. Now he has a place in the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.